Feeding The Moloch: On Crisis, Speculation and Public Housing Renewal in Victoria

On Crisis

It is widely acknowledged that Australia, similar to many countries in both the Global North and Global South, is currently witnessing an acute ‘housing crisis’. However, the crisis in Australia has been building to a cataclysmic-like pressure point for the better part of two decades, arguably under the successive neglect of governments. As of July 2023, the situation seems dire; the national vacancy rate is 0.9%. The demand for affordable, accessible housing far outstrips supply in our capital cities and regions, and the twin spectres of inflation and stagnant wage growth further induce housing stress on all tenure groups. Australian housing prices are both overvalued and unaffordable. The ratio of house prices to incomes and rents in Australia is at the highest in OECD countries since 2003. By late 2021, Australia's median national house price to income ratio had ballooned to 12.1, compared to 5.1 in the UK and 5.0 in the US. This is despite both comparable Anglocentric countries suffering their unique housing crises. As many argue, an inability to access secure affordable housing is the main driver for inequality in Australia. At the same time, as the crisis worsens, the most significant intergenerational wealth transfer in the country's history shows signs of cementing a two-tier class-based status quo between those who can and cannot access housing.

Australia’s relationship with housing since colonisation has been deeply problematic. Longstanding colonial practices premised on terra nullius not only continually reject Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples epistemological perspective but actively engage in systematic erasure, displacement and dispossession of sovereign First Peoples' rights and connection to Country. By extension, the cadastral property system as a colonial invention has been the dominant tool by which the colonisation of Australia has been enacted, coupled with repeated ongoing violent enforcement of hegemonic power. Fundamentally, how property is framed as part of the settler myth-making of ‘Australia’ continues to reject ancient and enduring pre-settler systems of law and further disenfranchises First Peoples. It is a lamentable case in point that concerning the housing crisis, a 2022 AHURI report into Indigenous homelessness found the Indigenous homelessness rate is ten times that of non-Indigenous people, with one in 28 Indigenous people homeless at the time of the 2016 census. Furthermore, the report found that "a continuity of dispossession, racism, profound economic disadvantage and cultural oppression shapes the lived experience of many Indigenous Australians today". The 2021 Census found that 1 in 5 of those experiencing homelessness were Indigenous. Indigenous housing is a crisis-within-a-crisis and a long-existent symptom of the wider neo-colonialist housing policy setting we find in Australia.

'DeFlat' Kleiburg, Amsterdam, NL by NL Architects + XVW Architectuur, 2011-2016. Photo: Marcel van der Burg.

Dismantling Public Housing Renewal

Decades of overtly neoliberal sympathetic and populist vote-buying public policy have created the perfect storm in the form of a perpetually propped-up speculative housing bubble. In what we might consider civil society, long gone are the utopian Menzies-era ideals of housing for all as espoused by the embedded liberalism of the Keynesian post-war period. Construction of new public housing dwellings is currently at its lowest rate in over 40 years. Existing public housing stock is chronically underfunded and endures an ongoing excruciating demise. In the Australian context, the legacy of ‘The Pruitt-Igoe Myth’ continues to reverberate in policy-making echo chambers. At the same time, there are concerted and ongoing efforts by state governments to shed direct responsibility for public housing through privatisation and aggressive asset transfers under the guise of ‘public housing urban renewal’ programs. Championed by advocacy coalitions comprising (but not limited to) state governments, private developers and more recently, not-for-profit Community Housing Providers (CHPs).

In Victoria, renewal programs such as the Public Housing Renewal Program (PHRP), in particular, have been criticised as fundamentally flawed for several reasons. Examples including a project brief that is premised on the paternalistic presumption of the benefits of ‘social mix’. Colloquially referred to in the property industry as the ‘salt and pepper’ approach to social housing. The non-evidence-supported strategy of co-locating social housing tenants with their ‘better off’ private market renter/owners aims to achieve social capital transfer and foster a ‘community’ amongst different socio-economic demographics. Critically, we must analyse ‘social mix’ agendas against the problematic yet dominant historical backdrop of Antipodean assimilation and forced Anglo-Saxon homogeneity. Regarding functionality and programme, despite PHRP projects seeking to ‘renew’ public housing stocks, there is a lack of demonstrated significant improvements to housing stocks. For example, the Victorian ‘Big Build’ housing projects that fall under the PHRP program generally mandate a minimum 10% increase in social dwelling numbers yet result in an overall reduction in the total number of beds per dwelling compared to existing demolished project stock. In this example, adding additional private ‘market’ rental stock or the inclusion of the minimal number of ‘affordable’ dwellings as part of the overall project does little to offset the demolition of existing public housing stock, the fracturing of existing communities and displacement of residents (regardless of their ‘rights of return’) once the projects are completed, to say nothing of the significant sustainability concerns such tabula rasa methods employ.

Transformation of 530 dwellings, Block G, H, I, Grand Parc Estate, Bordeaux, France by Lacaton & Vassal, 2017.

Photo: Philippe Ruault.

Contemporary States of Speculation

The state itself, as the principal actor in the housing space, has more incentive to maintain political and economic order than try to solve the ongoing crisis, evidenced most recently by the lack of substantive policy in the recent 2023-2024 Federal and Victorian State budgets. Despite the historical performance of the initial Commonwealth-State Housing Agreements (CSHA), consider, for example, that the first 10-year CSHA was able to build nearly 100,000 public housing dwellings between 1945-1955 alone. There seems little appetite to revive the commonwealth's role in affordable housing delivery. The only signature federal policy is the nebulous $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) with the somewhat opaque goal to “fund acute housing needs on an ongoing basis” and build 30,000 new social and affordable housing in its first five years, albeit with the caveat that expenditure is dependent on the fund itself making returns, essentially taking a wager on the ASX and continued economic growth. Even at the level of federal public policy, actions seem entirely couched in the notion of Australia as the ‘lucky country’, despite the housing crisis in Australia as an exemplar of free market failure in providing a basic necessity; the human right to adequate housing, for the Federal government it’s a case in point of a better tomorrow, tomorrow.

With recent discussion of the housing crisis showing no sign of exiting the news cycle, National Cabinet has agreed to boost the 2022 National Housing Accord target from 1 to 1.2 million new homes for the period 2024-2029. At the same time, National Cabinet has flagged a ‘National Planning Reform Blueprint’, targeting what it sees as dysfunction in local and state planning policies. When the political messaging of a complex issue is simplified to ‘insufficient supply’ and ‘bureaucratic red tape’, panacea solutions seem to have rational appeal, yet only time will tell how this will be achieved without a tangible and nuanced delivery pathway. Finally, moves by the National cabinet to strengthen tenancy laws would be a positive signal if those laws weren’t already legislated in most states, becoming, at worst, a cost-free quick political win for the Federal government and, a best, a PR mechanism to help build appeal for the emerging Build To Rent (BTR) sector tied so heavily to domestic and international institutional wealth.

The resulting instability of a developed economy continually relying so heavily on its property sector creates a situation where speculative property ownership (thinly masked under the auspices of “the great Australian dream”) creates a “too big to fail” relationship between homeowners, financial institutes and elected governments. This is even though homeownership rates are in decline, having peaked between the 1940s-70s and having slumped to 67.1% in recent years. We see the ongoing demonisation of other tenure models such as private renting or social renting in lieu of the lavishly praised ‘home owner’, here ‘Howards Battlers’ are lionised whilst those who find themselves long-term renters (regardless of demographic) are considered abject failures, those trying to access social housing; particularly public housing are stigmatised as ‘less than’. The 'Hegemony of tenure' prioritises homeowners in policy-making, portraying home ownership as moralistically superior and housing as a speculative asset rather than a basic human need or infrastructure. The ‘reverse welfarism’ of Australian housing policy undermines legitimate attempts to de-escalate the crisis and continues to privilege the landlord class while sacrificing society.

In contrast, it would be helpful to consider the different perceptions of Viennese housing policy. In the Austrian context, 40% of houses are of rental tenure. In what has come to be labelled the ‘affordable housing Mecca’ of Vienna, this number rises to an incredible 80% of dwellings in rental tenure. This is backed not just by one of the world's largest public (and affordability-regulated) rental housing systems but a local policy and media setting where the rights of rental tenure are at the forefront of political debate and enshrined in law.

The vast majority of Australians (even long term-renters) have been coaxed to view housing as a speculative asset (a non-productive one at that) rather than to conceptualise housing as a fundamental right for all. Richard Denniss, economist and director of The Australia Institute, applies the useful metaphor of the current housing crisis as a kind of ‘Kabuki Theatre’, in particular reference to the recent push in Governmental language for ‘making housing affordable’. It may seem reductionist, but the fundamental core issue in the Australian housing crisis is not a total lack of supply; instead, house prices are simply too high. If public policy isn’t making prices fall, then those policies can’t make things more affordable. What could be more Helleresque?

Property ownership here, particularly in our charged media landscape, is not framed as ‘building a home’ as much as a rush to ‘get on the property ladder’ that paradoxically only lets you ascend the rungs, less the whole house of cards comes crashing down. Here to quote researcher Chris Martin of UNSW’s City Futures Research Centre, the property investor is cast as the self-made ‘clever Odysseus’ who achieves self-realisation and ‘financial freedom’ by harnessing the transformative leverage of property ownership. The hegemony of this discourse cannot be dissuaded. It permeates throughout any housing conversation. Those without the social, financial or cultural capital to enter the housing market are stigmatised, at best, patronised as ‘uninformed’ youths or those who ‘missed the boat’ of favourable financial conditions. At worst, paternalistically as ‘undeserving’ of adequate housing due to their perceived individual moral failings; vocally, these might be expressed along classist lines of employment, education or welfare reliance. More insidious biases quietly voiced abound along racist, sexist, ableist or ageist lines.

The culture of home ownership in Australia is both manufactured and politically expedient. To malaprop an idiom, the best time to buy a home was thirty years ago. The next best time is today. For many, the family home (safely not included in current aged pension asset tests) is considered the quintessential Australian retirement nest egg. When the time comes to leave this mortal coil, this asset class becomes the primary driver of the intergenerational transfer of wealth. Here we see the antithesis of the Chinese proverb, “One generation plants the trees, and another gets the shade.” Sexual morality and ascetic aspirations aside, we perhaps shouldn’t be surprised that the Catholic church introduced clerical celibacy laws in response to the potential for the concentration of wealth in the form of ecclesiastical property being passed down clerical lineages. As impolite as it may be to say out loud, the corrosive and divisive nature of this en-masse intergenerational transfer of wealth cannot be understated, and is in itself a serious threat to a better future for Australia.

The Speculative and/or Ethical Architect

There is a secondary ethical crisis for architects and other design professionals involved directly in providing housing (affordable, social, speculative or other). Are our professional and personal actions directly contributing to and exacerbating the crisis? Manfredo Tafuri's comments related to the Progetto di crisis seem relevant once more:

“Utopias don’t exist anymore. Engaged architecture, which I tried to make politically and socially involved, is over. Now the only thing one can do is empty architecture. Today, architects are forced into either being a star or being a nobody. For me, this isn’t really the “failure of modern architecture”; instead, we have to look to what architects could do when certain things weren’t possible and when they were.”

Indeed, it isn’t good enough to merely greenwash our latest architectural projects in a vain attempt to win accolades whilst ignoring the underlying instrumentalism of our professions to capitalism's corrosive social effects. Suppose architecture has completely surrendered itself to the post-political, as some have argued, might there be any minor redemption arc for the discipline, particularly in the Australian context and in light of the ever-worsening crisis? Is there a space for architects to more critically assess and actively advocate for housing policy reform? Here I am reminded of the lamentable recent anecdote of a senior public servant (and former architect) commenting there was “no role for politics in architectural work”, eviscerating their credibility as a prominent paid advocate in both spheres of work.

Arguably, Australia (and Victoria in particular) indeed has a rich legacy of architects attempting to ‘make political’ issues relating to housing, be it Robin Boyd's twin aesthetic/Australian ethos critique of the banalities of suburbia in The Great Australian Ugliness (1960) or his work with the Small Homes Service (1947-1953), which sought to advocate for the common good through the delivery of modest, environmentally sensitive, affordable and accessible home designs. Another example would be prolific Architectural historian Miles Lewis’ prominent advocacy role concerning the Carlton Urban Renewal Scheme (1972) and ongoing participation with other so-called ‘trendies’ in community opposition to inner and middle suburban development they deemed contextually destructive. With architect Maggie Edmonds there is the example of her RAIA-endorsed alternative plan to the Brooks Crescent redevelopment, which sought preservation, rehabilitation of houses, building new dwellings and inclusion of community facilities such as a kindergarten and creche (what Delores Hayden might call a more care-driven approach) to show that retention and renovation of existing housing stock was not only possible but provided for a desirable alternative way forward.

St Georges Road Infill Housing. Photo: Gregory Burgess.

We should reflect on Architect John Devenish's experimentative work heading the Victorian Ministry of Housing infill housing program (1982-1985), which sought to purchase existing housing stock and, through local architectural practices, restore them in an urban contextually sensitive manner, directly attempting to address the bubbling social stigma attached to social housing and public housing bodies. Even if this was tied directly to the Ministry's institutional renewal and repositioning of Public Housing as a temporary stepping stone to home ownership, an essential talking point to the eventual dismantling of public housing. The program’s distinctly postmodern approach is directly inspired by the successful efforts of the Berlin Internationale Bauausstellung IBA (1979-1989).

In more recent years, we’ve seen the Office of the Victorian Government Architect (OVGA) run a series of design competitions and pilot projects (Living Places, Habitat 21 and Future Homes) seeking to present alternative housing strategies and provide a platform for professional discourse in light of the ongoing broader housing market failure. Finally, there is OFFICE, a not-for-profit design and research practice that proposed an alternative ‘Retain, Repair, Reinvest’ model for the Ascot Vale Estate and Barak Beacon Estate. The latter now sadly demolished under the previously discussed State governments Public Housing Renewal Program (PHRP) despite public protest and occupation of the site reminiscent of the 2016 Bendigo Street housing dispute.

Replicable apartment proposals by Design Strategy in collaboration with IncluDesign win Victoria’s Future Homes competition. The Future Homes Project © Design Strategy Architecture + IncluDesign, 2020.

The examples given here are few, but there are many more historical examples of practising architects (some memorialised, others forgotten in the local architectural canon) utilising their knowledge, skills and networks to facilitate positive change in the face of the emerging housing crisis. The solutions to the housing crisis itself are not unknown. Particularly in the last decade or so, there has been an extensive academic focus on the emergence of the nature of the crisis and pathways toward fundamental change. See, for example, the Transforming Housing Project (2014-15), which outlined several policy, investment and demonstration projects supported by a litany of research and case studies or the recently published Housing Policy in Australia: A Case for System Reform (2020) which outlines the historic policy setting which has fueled the crisis along with significant commentary for potential systematic overhaul. The potential for this plethora of earnest and, importantly, evidence-based policy reforms is stymied by a lack of political will. If this cannot be successfully challenged, how can we achieve a future housing condition predicated on equity, intensity and densification of our cities?

Despite repeated calls for reform by policy advocates, little has been done to unwind the overheated speculative nature of Australia’s institutionalised housing sector. There seems to be a dwindling of architectural conviction in confronting the speculation fueling the housing crisis in recent years, both in action and advocacy discourse. Could this reflect the privileged position of the Australian architectural industry's dominant voices? For many industry luminaries, the conditions behind Australia’s housing crisis have benefited them, as they have turned their architectural savvy and social capital into capital accumulation and, by extension, increased wealth and clout.

If architecture itself is indeed post-political, as some suggest, then does that reduce the profession's force majeure role to merely myopic aesthetic criticism? Architecture as a profession has a long tradition of identifying with our patron clients while distancing ourselves from those that cannot afford that same patronage, not to mention a torrid institutionalised legacy of exploitation within practice and the academy. In this respect, the architect's often classist position is not beyond scrutiny or reproach in the context of the ongoing and intensifying housing crisis. Is the limit of our civic engagement that we might sometimes seek to design a seemingly ‘democratic’ institution or public building, putting the literal facade of civility on chimaera-like neo-colonial institutions operating in previously discussed contested settler spaces? Is the future of architecture as a profession in regard to the Australian housing crisis just the ongoing proliferation of Tafuri’s ‘empty architecture’, or can we find a way back to contributing to that quasi-utopian ideal of politically and socially ‘engaged’ architecture that supplants the current ‘Kabuki Theatre’ of crisis?

-

Banner, Stuart. “Why Terra Nullius? Anthropology and Property Law in Early Australia.” Law and History Review 23, no. 1 (2005): 95–131.

Benson, Eleanor, Morgan Brigg, Ke Hu, Sarah Maddison, Alexia Makras, Nikki Moodie, and Elizabeth Strakosch. “Mapping the Spatial Politics of Australian Settler Colonialism.” Political Geography 102 (April 2023): 102855.

Blunt, Alison, and Robyn M. Dowling. Home: Key Ideas in Geography, 2nd ed. London; New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022.

Burke, Terry, Christian Nygaard, and Liss Ralston. “Australian Home Ownership: Past Reflections, Future Directions.” AHURI Final Report. April 2021: 58-63.

Burns, Karen, and Paul Walker. “Publicly Postmodern: Media, Image and the New Social Housing Institution in 1980s Melbourne.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 32, Architecture, Institutions and Change, 68-81. Sydney: SAHANZ, 2015.

Capp, Ruby, Libby Porter, and David Kelly. “Re-Scaling Social Mix: Public Housing Renewal in Melbourne.” Journal of Urban Affairs 44, no. 3 (2022): 380–96.

Chong, Fenneen. “Housing Price and Interest Rate Hike: A Tale of Five Cities in Australia.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16, no. 2 (2023): 61.

Cook, Julia. “Keeping It in the Family: Understanding the Negotiation of Intergenerational Transfers for Entry into Homeownership.” Housing Studies 36, no. 8 (2021): 1193–1211.

Daley, John, Brenan Coates, and Trent Wiltshire. “Housing Affordability: Re-Imagining the Australian Dream.” 2018.

Frazee, Charles A. “The Origins of Clerical Celibacy in the Western Church.” Church History 57 (1988): 108.

Groenhart, Lucy, and Terry Burke. “Thirty Years of Public Housing Supply and Consumption: 1981– 2011.” AHURI Final Report no. 231. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, 2014.

Gurran, Nicole, and Peter Phibbs. “Are Governments Really Interested in Fixing the Housing Problem? Policy Capture and Busy Work in Australia.” Housing Studies 30, no. 5 (2015): 711–29.

Hall, Bianca. “‘They’ll Have to Carry Me out’: The Residents Fighting to Save Their Public Housing Estate.” The Age. March 19, 2023.

Hansen, Amelia. “Exploring the Shortage of Specialist Disability Accommodation in Australia.” Maple Services. March 1, 2023.

Hayden, Dolores. “What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work.” Signs 5, no. 3 (1980): 170–87.

Hyde, Rory. “What Would Boyd Do?: A Small Homes Service for Today.” Architecture Australia 3, no. 107 (2018): 71–73.

Kolovos, Benita. “Victoria’s Social Housing Stock Grows by Just 74 Dwellings in Four Years Despite Huge Waiting List.” The Guardian. March 16, 2023.

Langton, Marcia. “Law: The Way of the Ancestors.” January 2023: 16-21.

Legislative Council Legal and Social Issues Committee (Vic). Inquiry into the Public Housing Renewal Program: Report. Melbourne: Parliament of Victoria, June 5, 2018. https://apo.org.au/node/175096.

Madden, David J., and Peter Marcuse. In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis. London; New York: Verso, 2016, 119-120.

Martin, Chris. “Clever Odysseus: Narratives and Strategies of Rental Property Investor Subjectivity in Australia.” Housing Studies 33, no. 7 (2018): 1060–84.

Martin, Chris. “Security and Renewal in Australian Public Housing: Historical Representations and Current Problems.” Urban Policy and Research 39, no. 1 (2021): 48–62.

Nygaard, Christian, Simon Pinnegar, Elizabeth Taylor, Iris Levin, and Rachel Maguire. “Evaluation and Learning in Public Housing Urban Renewal.” AHURI Final Report, no. 358 (July 2021).

OFFICE. “OFFICE – Retain Repair Reinvest.” Accessed May 28, 2023. https://office.org.au/project/retain-repair-reinvest/.

Parliament of Australia. “Housing Australia Future Fund Bill 2023.” Text. Australia. Accessed May 28, 2023.

Pawson, Hal, Vivienne Milligan, and Judith Yates. Housing Policy in Australia: A Case for System Reform. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2020.

Peverini, Marco. “Grounding Urban Governance on Housing Affordability: A Conceptual Framework for Policy Analysis Insights from Vienna.” Partecipazione e Conflitto 14, no. 2 (2021): 848–69.

Porter, Libby, and David Kelly. “Dwelling Justice: Locating Settler Relations in Research and Activism on Stolen Land.” International Journal of Housing Policy (2022): 1–19.

Tafuri, Manfredo. Interview with Richard Ingersoll. “Non c’è critica, solo storia.” Casabella no. 619-620 (1995): 98.

Tedmanson, Deirdre, Selina Tually, Daphne Habibis, Kelly McKinley, Alwin Chong, Ian Goodwin-Smith, Skye Akbar, and Kate Deuter. “Urban Indigenous Homelessness: Much More than Housing.” AHURI Final Report, no. 383 (August 2022).

Visontay, Elias. “Living with Density: Will Australia’s Housing Crisis Finally Change the Way Its Cities Work?” The Guardian. April 15, 2023.

White, Iain, and Gauri Nandedkar. “The Housing Crisis as an Ideological Artefact: Analysing How Political Discourse Defines, Diagnoses, and Responds.” Housing Studies 36, no. 2 (2021): 213–34.

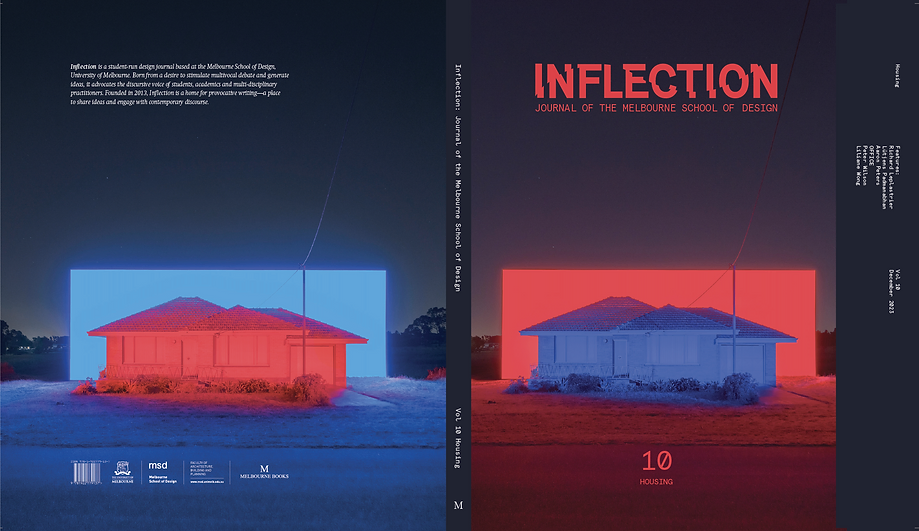

Available in Inflection Vol. 10 “Housing”

This paper explores the "feeding of the Moloch" that is the housing crisis in Australia. It argues that the crisis is the result of decades of neoliberal policies, speculation, and the dismantling of public housing. The paper examines the Victorian government's Public Housing Renewal Program (PHRP) and critiques it for its lack of evidence based policy, focus on social mix, and failure to address the crisis. Additionally, the paper critiques the speculative nature of the housing market and the government's inaction. It concludes by calling for architects to take action and contribute to solving the crisis.